A Closer Look at the Rehoboth Beach Bigbelly Trash Can

Earlier this summer, the City of Rehoboth Beach placed the Bigbelly trash cans in service at strategic locations throughout town. “The Bigbelly units were first considered when trying to brainstorm ideas on how the city’s refuse collection operation could be made more efficient,” says Sharon Lynn, city manager.

The city has had public works crews working from 5 a.m. to 10 p.m. collecting refuse from all of the public areas where cans are present. The crews travel across the city all day, she notes, stopping at every can to check and determine if they are full. “As you can imagine, the time of day, day of the week, weather, events going on, and time of the year, all impact the collection frequency,” Lynn points out.

With more people in town, collection operations can sometimes move slowly. The slower the operation, she observes, the more likely it is that cans may overflow. “In an effort to improve the operation,” Lynn said, “we reached out to Bigbelly…” and after several meetings with the Bigbelly team, she said she believed this was an excellent solution to present to the city commissioners during budget discussions.

These units are solar-powered, self-compacting and self-contained which eliminates overflow and windblown litter. The cans occasionally cycle through a compaction cycle. The compactor enables the can to hold up to five times more refuse than traditional cans, she said. But the cans still use plastic bags.

Additionally, the stations communicate real-time data to city staff via a mobile app. The data enables crews to avoid making trips to areas until they receive a notification that a collection is needed, she says. The network also generates reports that include maintenance needs, historical collection information by location, average time it takes for a unit to be ready for a collection and determine days and times when the units are being used the most.

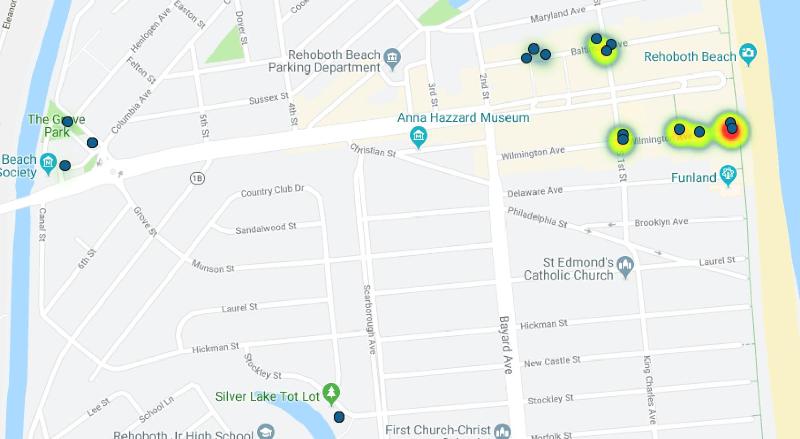

According to the data, among the heaviest used is the Bigbelly pair at Wilmington Avenue and the boardwalk.

Lynn says the data can be used to help the city adjust Bigbelly placements based on demand, tweak collection routes and staffing and overall, reduce the number of trips made and time taken to collect refuse.

The total project cost is about $134,000 which will be paid over five years, at a cost of roughly $26,000 per year, Lynn said. The city purchased 18 units to evaluate at various locations to determine if some areas might be better suited for them than others.

Additionally, this will be a trial program to determine whether expected outcomes become a reality, she said. Included in the total of 18 units are two recycling units which will serve as a trial program to test the expansion of recycling into public spaces. On July 12, the recycling units were placed at Grove Park and at Stockley Street Park.

Evan Miller, the city’s projects coordinator, says a recycling grant was submitted to DNREC with the hopes of receiving funds to help cover the cost of the two recycling units.